Before we begin, I must tell you that the mystery of the magnet man remains unsolved. That can’t possibly disappoint you, because you don’t know anything about the magnet man – you can’t possibly be expected to care. I’m trying to save you from the feelings I felt. Because I cared. For a sweaty, obsessive week in September culminating (coincidentally) in the Queen’s death, I was consumed. Then, disappointed. One month on, the mystery of the magnet man remains unsolved.

It started simply enough. An editor asked me to write an article about souvenirs – fun! Good! Not the kind of thing that could possibly drive someone mad! The editor wanted me to speak with collectors – which I did – but I also wanted to speak with a manufacturer. I wanted to know how the world’s most enduring landmarks were shrunk into three dimensional ceramics to be stuck on the fridge. There was something about the way you could find this kind of magnet all around the world that intrigued me – who was making them? Why? How?

So I found the magnet man’s website; I emailed him and waited for a reply.

I’m going to give the magnet man a fake name for privacy reasons, even though I fundamentally believe him to be undoxable (or more likely but less interestingly, dead). Owen Carlton has made fridge magnets for some of Britain’s biggest and best tourist attractions. Even if you haven’t seen his magnets, I bet you can picture them: a clay pillar here, a sticky-out turret there, a little black disc glued to the back.

Owen Carlton’s website looked a little outdated, sure, but at the very bottom it said: “© 2021”. I was pleased that the “contact” page contained an actual email address and not the dreaded white box. But later that day, I saw that my email had bounced back.

No problemo, is the kind of thing I probably said to myself, although not yet deranged. There are other ways of contacting people. Zuckerberg, pallid and plotting though he may be, has made it easy to find anyone: I’ve used Facebook to track down a couple who got a question embarrassingly wrong on The Million Pound Drop in 2011 and a boy – now a man – who once said “I like turtles” on the local news.

But Owen Carlton’s website didn’t include links to any social media profiles. What it did have, unusually, was an entire page dedicated to promoting nearby businesses, one of which was apparently “just down the road.” I emailed a few of these businesses asking if they knew Owen, but I heard nothing back.

When I rang up the owner of the “just down the road” business a few days later, he said – curtly, in a voice I pretended was masking secrets – “I’ve been here nearly 30 years. There’s no one nearby with that name.”

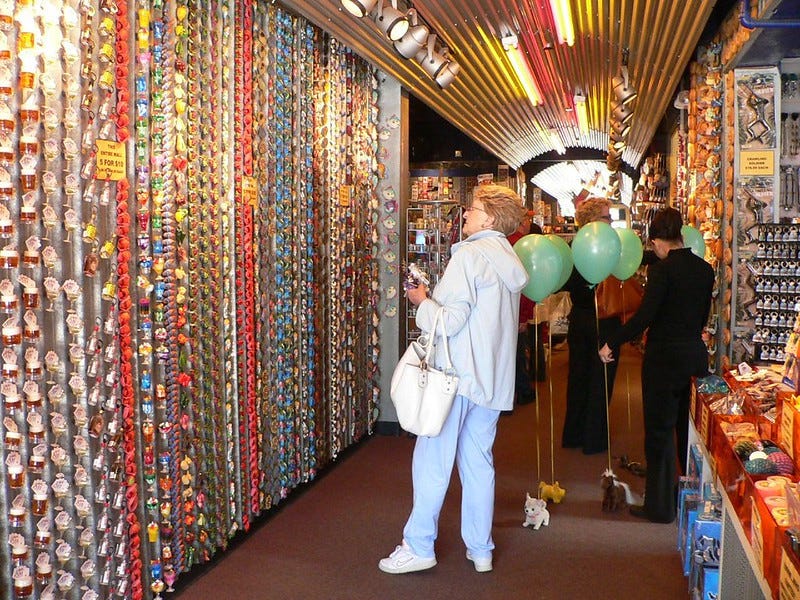

Photograph by Windell Oskay

Before I got to that point, I had already tried to find Owen Carlton’s business address. His website said he was located in REDACTED, but there was no business by that name in or near REDACTED at all. I searched Companies House. I searched LinkedIn to see if any employees had listed themselves as working for Owen Carlton, now or in the past. I posted on REDACTED’s community Facebook pages to ask if anyone knew of the business.

I flicked through the phonebook – at least, the online version. I phoned two numbers that used to be associated with Owen’s business: one was disconnected, another rang tantalisingly on and on and on.

In the midst of a thousand tabs, I eventually found an address. It was on a business directory website, and though it was in a different town to the one listed on Owen’s website, it was definitely him. I wrote a letter. I stamped it and sent it. I heard nothing back.

Promisingly, the site listed one other employee associated with Owen’s business, and she had a reasonably unusual name. We’ll call her Carole Thunderhead.

I Googled Carole and found she’d once been quoted in the local newspaper in a story about her church. I found a fellowship group she ran, and I found one of the church’s bulletins from April with her name and number listed as an event organiser at the bottom. With apologies ready in my cheeks, I gave Carole a call.

“Hi, my name’s Amelia and I’m a journalist. I’m sorry for the strange nature of this call but…” I asked if she used to work for Owen Carlton; she said yes. Breathlessly, I asked if she was still in touch.

“Crfhfhfhf,” came the reply, “crrk qqqurrr kskkksk”. The signal was terrible. When I got her back, that’s what she said: “Sorry, the signal’s terrible.” Carole wasn’t in touch with Owen Carlton. She hadn’t seen him in 20 years. That seemed like a terribly long time.

“So, do you think he’d be… around 70?” I said, trying to subtly inquire as to whether he might be dead. “Yes, I suppose so,” she said. Feeling like a degenerate for bothering a church-related stranger for non-church related reasons, I said my goodbyes.

Later, I texted Carole saying that, if she knew of anyone else who might be able to reach Owen, please let me know. I heard nothing back.

While I was supposed to be doing work, eating meals, texting friends, taking showers, I looked for obituaries. I contacted the landmarks that Owen Carlton had made souvenirs for. Most didn’t reply. Two said they couldn’t find any contact details for him in their books. I used the Wayback Machine to see what Owen’s website used to look like and started emailing local businesses that he used to recommend, one of which sold dance poles for “work, leisure or pleasure – the choice is yours.”

Funeral notices told me that other Owen Carltons have been and gone, but the magnet man seemingly still lives.

Photograph by Bev Sykes

It’s hard to express how little Owen mattered to my story by this point. I’d already spoken with a nice man named Charles who makes Lederhosen aprons and London bus-shaped bottle openers. My deadline was fast approaching. Even if I did get Owen Carlton on the phone, would he add to the piece? In my most ungenerous moments, I thought that he’d be dull.

Still, I kept searching. I kept searching because this had never happened to me before. As a journalist, I pride myself on tracking people down. Once – for this very newsletter – I found a woman who had been on Changing Rooms in the year 2000: the show never mentioned her last name, but I found it in a railway magazine she’d written a letter to in 2002. The letter didn’t even mention Changing Rooms! They don’t give journalism awards for that kind of thing – but shouldn’t they? Shouldn’t they?

In the past I’ve had people not want to talk to me, sure, but this was different. None of my messages had actually reached Owen Carlton – the address I’d sent a letter to was 20 years out of date. By this point, I’d enlisted other journalists to help and one thought she’d found him on Facebook, but it turned out to be another Owen Carlton, one who’d worked at Bacofoil.

I briefly convinced myself that Owen Carlton had moved to Brazil, and WhatsApped a man I thought to be his new business partner. Two ticks of acknowledgement appeared on my screen, but I heard nothing back.

I started interrupting conversations that weren’t about Owen Carlton to talk about Owen Carlton. I drew friends into my obsessive orbit. One of them found out that Owen once sold magnets with Disney. It was hard to believe, but there were eBay listings of Owen Carlton’s magnets and the pictures of the boxes had © THE WALT DISNEY COMPANY on the back. How could the magnet man have worked with one of the biggest corporations in the world, and yet no trace of him stuck?

I started ringing O Carltons in the phonebook. “Nope, not me,” came most of the replies. One woman answered the phone and said she didn’t think her husband had ever made magnets, but she better put him on the phone to check.

“Sorry I can’t help you,” he said – I could hear the hum of the telly in the background and could almost see it seeping into plush chintz armchairs. “I wish that was me,” the wrong O Carlton joked, his voice frail with age, “I might’ve made some money out of it.”

I wrote and submitted my souvenirs piece and had to move on. The trouble with freelance journalism is that all of this was all unpaid, wasted time. I ended my search for the magnet man not a step closer than where I started. I told you that the mystery was unsolved. It’s not my fault you’ve got this far.

Perhaps I am not supposed to speak with the magnet man. Perhaps our destinies are not attracted like a St Paul’s magnet and a metal fridge. Perhaps we are more like two south poles in a science class, repelling each other every time we come close.