The untold story of Gwyneth Paltrow’s body double

Content warning: this issue contains descriptions of weight loss, fatphobia and eating disorders.

In July, TikTok started feeding me clips of Shallow Hal. I hadn’t seen the 2001 rom-com since I was a child, but I knew it would be problematic through 2023 eyes. The premise alone is teeth-clenching: womaniser Hal (Jack Black) is hypnotised so that he only sees inner beauty, meaning he (and here’s come the joke!) falls in love with a fat woman. Incidentally, inner beauty looks like Gwyneth Paltrow.

I was so familiar with the lore around Paltrow’s role that I didn’t realise until rewatching that she wasn’t the only person who played Hal’s love interest, Rosemary, in the film. Paltrow has spoken about wearing a “fatsuit” for the part – describing it as “humiliating” – but fatsuits can only go so far. With my phone inches from my face, I realised: Oh, that’s a real woman’s upper arm the camera is focusing on. That’s a real woman’s thighs in those bikini bottoms. That’s a real woman who has been decapitated so her body can be played for laughs.

Since it premiered, people have written plenty on the cultural impact of Shallow Hal and its negative contribution to society. But here was someone at the centre of the story who had largely been ignored. Online, I could only find one 2001 interview with Paltrow’s body double, and it ran at just 464 words.

I wanted to know: How did this “second Rosemary” feel when filming, and how did the movie change her life afterwards? Sure, she’s just one person – but I thought she would be the one person who was most affected by the fatphobia in Shallow Hal. Ultimately, I came to find out it wasn’t that simple.

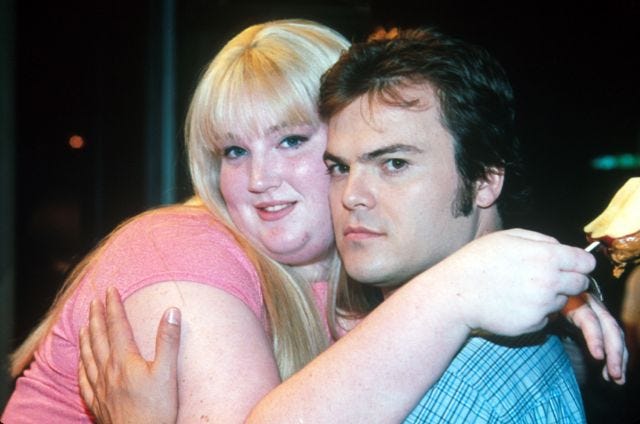

Ivy Snitzer and Jack Black in 2001. Credit: Glenn Watson, Alamy

Ivy Snitzer has screen presence – even on Zoom. Now a 42-year-old insurance agency owner in Philadelphia, Snitzer has a natural storytelling ability. She sports safety pin earrings, a nose piercing, reddish-purpleish hair and a black choker. She has lost a significant amount of weight since playing Rosemary in Shallow Hal.

Twenty-or-so years ago, 20-year-old Ivy Snitzer was an LA-based acting student with aspirations to become an actor or comedian. “Mostly, I just wanted to be funny,” she tells me. One day, a friend from her improv class called her up because he’d heard about “this thing.” To this day, Ivy doesn’t know the wording of the Shallow Hal casting call. Without asking any questions, she hopped into her friend’s car and drove to a room where casting agents “took a bunch of pictures.” A day later, Ivy had a callback – she was invited to sit down with the film’s directors, the Farrelly brothers, and “just talk.”

“They just wanted to know that I was somebody who was cool to work with, friendly and fine,” Ivy says. Within the hour, she’d got the job. Ivy had no negative reactions to learning the premise of the movie, which felt progressive to her at the time. “At that point, if you saw someone obese in a movie, they were a villain,” she says, whereas Rosemary “was cool, she was popular, she had friends.” Ivy also has zero negative memories of shooting the movie in North Carolina.

“It was so exciting. It was just fun to be part of a movie – there’s so few people who actually get to do that in the world,” she says. The cast and crew “treated me like I really mattered, like they couldn’t make the movie without me” and Ivy was made to “feel really comfortable” when her body was being filmed. Jack Black was “a delightful person” and Gwyneth Paltrow was “really nice” (she regularly complimented Ivy’s acting). It “didn’t occur” to Ivy to be offended by the movie’s jokes about her size, because she made those kinds of jokes, too.

But another thing didn’t occur to Ivy, and it came to trouble her greatly when the realisation hit. “It didn’t occur to me,” she says with a sigh, “that the film would be seen by millions of people.”

Ivy at the Shallow Hal premiere. Credit: Tsuni / USA, Alamy

When Shallow Hal was released on 9 November 2001: “Oh my God, it was like the worst parts about being fat were magnified. And no one was telling me I was funny.”

To promote the film, Ivy was invited to do TV and magazine interviews – although this was initially exciting, she soon realised it was an open invitation to strangers, who started approaching her on the street. People were angry that Ivy had said, “it is not the worst thing in the world to be fat”; some claimed she was promoting obesity. One person found her address and sent her diet pills. There were love letters, too – someone mailed her a symphony they’d composed especially for her.

“I got really scared and I just got really small,” Ivy recalls. “I was like: maybe I’m done with the concept of fame, maybe I don’t want to be an actor. Maybe I’ll do something else.”

Ivy moved back to New York to live with her parents – she worked as a bartender, occasionally performed comedy, and was briefly a cater-waiter. Casting agents kept offering her roles but they were “mean”; “I didn’t want to play a woman who was so ugly and lonely she molested young boys because that was the only way she could get affection.” This, Ivy says, was the antithesis of why she had sought fame in the first place. “I just want to make people laugh, I don’t want to make people sad.”

The trouble – as I gradually discovered across two phone calls and multiple emails with Ivy – is that the story of her post-Shallow Hal life is sad. So much so, that she’s never really spoken about it with anyone, not even her husband. Although she talks to me about her experiences candidly and without hesitation, she also laments: “Usually, when I tell stories about myself, I only tell them because they’re funny!”

If you are enjoying this newsletter, please consider leaving me a tip. I write these issues for free and purchase images myself; editors don’t pay people to write about 22-year-old films for no particular reason. I believe there’s no right or wrong time to tell anybody’s story.

Less than two years after Shallow Hal debuted, “Rosemary’s body” was “technically starving to death.”

In 2003, Ivy got lap-band surgery, which reduced the size of her stomach and restricted what she could eat. But shortly after the procedure, Ivy’s band slipped, “and I got essentially a torsion, like dogs get and then die.”

The timing couldn’t have been worse – Ivy didn’t have health insurance, so she had to get a temp job at an asset management firm in Beverly Hills (she had moved back to LA with her comedy writing partner). Ivy had to wait out her probation period before she was given health insurance, meaning she spent three months unable to consume anything thicker than water without throwing up. She lived off electrolyte drinks and watered down nutritional shakes. “I was so thin you could see my teeth through my face and my skin was all grey.

“And I was just SO bitchy all the time. I kind of alienated a lot of my friends. My mother was also dying at the time. It was bleak. Humans shouldn’t have to experience how very bleak that particular time in my life was.”

Ivy became so malnourished that doctors were not able to perform surgery to remove her band; first they had to insert a PICC line to provide her with liquid nutrition. For four months, Ivy had to hook herself up to an IV bag every night after work to – as she puts it – “not die.” Ultimately, due to further complications, doctors gave Ivy a gastric bypass, removing part of her stomach. To this day, she has to eat “weird tiny portions” and can’t eat and drink at the same time.

I ask Ivy why she got the initial weight loss surgery. “I don’t know,” she says quietly before livening up: “Because I was supposed to! If you’re fat, you’re supposed to try to not be.” She cites writer Roxane Gay’s idea of a “good” fat person, someone who orders salads and never eats burgers in front of other people. Ivy thought getting the surgery meant she was being good.

I ask Ivy whether she thinks her decision to get weight loss surgery was connected to her negative experiences after Shallow Hal. She responds as though she’s never thought about it before.

“Huh!” she says. “Not really. No.”

Filming Shallow Hal was empowering for Ivy because of what happened offscreen, not on it. “Out of all of the fat people in the world that they could have hired for that job, they hired me, because of my personality,” she says. “Before, I had to fight really hard to be seen as a personality and not just my size.” Ivy says undergoing a weight loss procedure 15 months later wasn’t connected – it was more of a coincidence. A doctor told her she wouldn’t live to see 40 without surgery and she thought, “fantastic. Something that’ll fix it. That’s fine.”

Ivy’s history with her body isn’t straightforward – because nobody’s is. She first noticed herself gaining weight around the age of 10. She describes herself as part of the “ketchup is a vegetable generation” who was “randomly the first very obese person” in her family. She could brush it off when other kids were mean about her body but hated when adults tried to offer well-intentioned advice. She counted calories as a teen and dieting eventually transitioned into disorder. Restricting started to feel good. “I felt like I’d got some control over the situation that everyone was telling me to control.”

Yet by the time she was filming Shallow Hal, Ivy was insecure, sure, but she also felt confident. “I wasn’t body positive, because it didn’t really exist that way. I was kind of ‘me positive’, because I was like: I’m funny, that’s good enough!” Still, in an attempt to be “good”, Ivy ate healthily on set. During filming, a senior person in production hugged her and remarked that she was losing weight. Ivy was happy; he wasn’t. He reminded Ivy that, “this entire movie is based on you not losing weight!”

After filming, Ivy was committed to the idea of being “a good fattie.” “I hated my body the way I was supposed to,” she says, “I ate a lot of salads. I had eating disorders that I was very proud of.”

Post-surgery and before her lap-band slipped, Ivy expedited her weight loss by exercising excessively, purging, and restricting her calorie intake. “It didn’t occur to me that I was supposed to be ashamed of those behaviours, like a lot of people are – for me, I was supposed to be proud of them.”

When Ivy was overweight, people would avoid eye contact with her, but when she was at her sickest – so malnourished that she needed medical intervention to stay alive – “everything was so different.” People smiled at Ivy, moved out of her way and paid for her coffee. “It was really nice to be treated well.”

Ivy today. Credit: Ivy Snitzer

Sometimes, Ivy feels “scared and sad” that watching Shallow Hal may have made young overweight girls feel bad, but other times, she receives complimentary Instagram messages from women saying she was the first fat representation they ever saw on screen.

After her lap-band slipped, Ivy pulled away from her disordered behaviours – “[because] I couldn’t consume anything, my mindset became more about how much I could manage to consume, not how little.” Ivy gained weight after her second surgery and resumed socialising with friends – six months later, she met her husband, who “came over for a sleepover on the second date and kind of never left.” Today, the couple have a 13-year-old daughter who has never expressed a desire to watch Shallow Hal and therefore simply hasn’t. For her part, Ivy’s “not going to run out and rewatch it.”

In fact, the only time Ivy has seen the film was when it premiered. She wore an outfit her mum made, which meant, “I finally had a coat that had sleeves long enough.” She planned to sneak around the back but the cast encouraged her to walk the red carpet, “which, again, is extremely cool when you’re a 20-year-old kid.” Ivy doesn’t remember how it felt to watch the movie itself.

“I love that it’s a cool thing I did one time,” she says of Shallow Hal – it’s a fun story she tells over drinks, and while the movie was being made, she was very happy. “It didn’t make me feel bad about myself. Until you know, other people started telling me I probably should have felt bad about myself.”

The last thing I want to be is one of those people, but I call Ivy back a few days after our initial call. I say I’m struggling to get my head around the fact her weight loss surgery came so soon after Shallow Hal premiered and left her exposed; I say I’m struggling to understand how the latter wasn’t connected to the former.

“I know,” Ivy says, “I’m sure it was… I’m sure I wanted to be small and not seen. I’m sure that’s there, but I don’t ever remember consciously thinking about it.”

Today, Ivy doesn’t regret the surgery, doesn’t worry too much about eating, and likes to think she’s “found a lot of stability in between the two extremes” of her past. She has cheered on the rise of the body positivity movement and is inspired by her daughter’s outspoken generation. But Ivy’s story was never simple, so it doesn’t have a simple ending. In reality, her relationship to her body “changes every day.”

As I’ve written before and undoubtedly will again, real life resists a narrative. When it comes to our bodies and our diets, most of us don’t get the kind of straightforward, happily-ever-afters you see in films. Still, I’m struck most by something Ivy said towards the very end of our last call. The two sentences are an answer to a question – but I think they make the most sense stripped of all of that, left to stand on their own.

“I was always my personality,” Ivy told me. “I’ve always been a personality in this body.”

Eating disorders are disorders at any size. If you are affected by any of the issues in this article please visit beateatingdisorders.org.uk or call its adult helpline at 0808 801 0677.

UPDATE: In May 2021, I wrote a newsletter about Shauna, a Scrappy-Doo fan who tirelessly crafted a thorough and remarkable Wikipedia page for the fictional Great Dane puppy. Sadly, following the publication of my newsletter, Wikipedia editors removed Shauna’s work, arguing that it cluttered the page. Thankfully, she was able to save her episode summaries and add them to Scoobypedia. You can read them here.

If you enjoyed this story, please consider leaving me a tip at: www.paypal.me/AmeliaTait

Via PayPal, I hope that different people can donate at different times depending on whether a story resonated with them. Whether 10p or £10, I am grateful for your contribution!

♥

Logo by Karolinka Designs